THE METHOD

How To Play Songs

By Ear

Using Relative Pitch |

To play a song by ear in the truest

sense means to play any song melody that's running in your head,

• accurately

and in REAL TIME, as the notes are going by,

•

without looking at any printed music,

•

with little or no preparation,

•

a song you've never played before

When you play by ear

in this manner, there's no guesswork and (preferably!) no mistakes - no stops

and starts.

I assume that you already know how to play your musical instrument,

and if you are given a note name, you can quickly play that note. So, the challenge

here is to identify the notes that you hear in the song - the notes that you will

play.

NOTES AND INTERVALS

There are basically 12 notes in music. Each note has a PITCH

which is a measure of how high or how low the note sounds. The 12 notes are listed

here in an upward pitch sequence, from bottom to top: The

12 notes encompass one OCTAVE. The dots indicate that the 12-note sequence repeats

as you go upward or downward in pitch.

Notice that there are five notes

that have two names (the black keys on a piano keyboard). For example, the note

A♯ (A sharp) has the same pitch as B♭

(B flat); the note C♯ is the same note as D♭, etc.

Either name can be used. Sharps and flats are called ACCIDENTALS.

A

musical INTERVAL is the distance or spacing between two notes.

The smallest interval, the interval between any two adjacent notes in the above

list or between adjacent keys on a piano keyboard, is one HALF-STEP (HS) or

SEMITONE. Two half-steps make a WHOLE-STEP (WS).

12 half-steps

make one OCTAVE where the note sequence then repeats as you continue upward

or downward in pitch.

RELATIVE

PITCH

The Relative Pitch method makes use

of a fundamental property of popular music: | Popular

music is TONAL. In every song there is a note called the TONIC.

The tonic is often (but not always) the last note in the melody, where the song

comes to rest. |

If

you want to use relative pitch to identify a note in a song melody, you must

first identify the note's pitch position relative to the tonic.

Then, if you know the tonic and you've memorized the note sequence that goes with

the tonic, it's a simple matter to identify the note you are hearing.

You're probably wondering, How could anyone

possibly learn to do all this?? And do it quickly??

We can learn to

easily do this because the notes in all song melodies generally lie in one simple

pattern that we can learn to hear and identify.

THE SEVEN-NOTE PATTERN - THE MAJOR SCALE

The common pattern of notes in song melodies is the

second property of popular music:

| In

popular song melodies the notes generally lie within a universal SEVEN-NOTE

PATTERN. The pattern is the same in every song - not always the same seven

notes, but the same note relationships within the pattern. |

The simplest example of the seven-note pattern is this

note sequence:

where

the note C is the tonic.

This sequence of seven notes, beginning with

the tonic, is called a MAJOR SCALE.

Another

example is where

D is the tonic. Major scales are named by their tonic note

- so these two major scales are the C major scale and the D major scale. Often

major scales are written with the octave note at the end. Thus, the C major scale

can be written as this eight-note sequence:

| C

= D = E =

F = G = A =

B = C' |

where

the apostrophe denotes the octave C.

Likewise the D major scale can be

written as

| D

= E = F♯

= G = A =

B = C♯

= D' |

The

sequence of intervals between adjacent notes in a major scale is

| W

= W = H =

W = W = W =

H |

|

where

W is whole step, and H is half-step. This interval sequence defines the major

scale, as illustrated here with the C and D major scales:

EXERCISE:

Play both scales on your instrument. The notes in the D major scale have a

higher pitch, but can you hear that the two scales have a similar sound quality?

This is because within each scale the notes have the same pitch relationships.

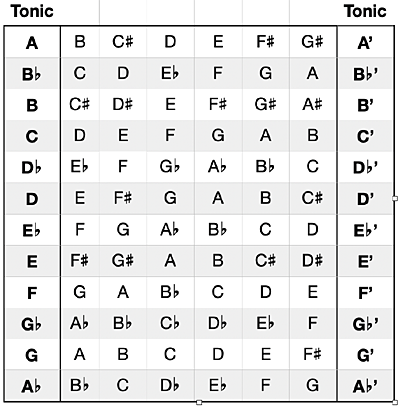

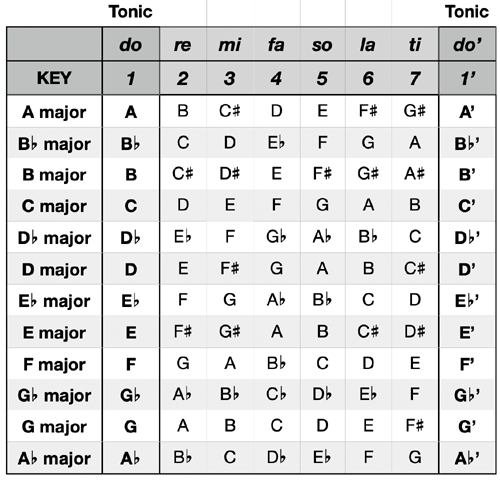

12 MAJOR SCALES

There are 12 possible tonic notes and thus 12 major scales.

The notes in the 12 major scales are listed

in Table 1.

Table 1 - The 12 Major Scales

|

[Note: There is also a F♯ major scale -

not shown here - which is equivalent to the G♭ major scale, but

the notes are written using sharps instead of flats. For example, the second note

in the scale is G♯ instead of A♭.]

EXERCISE:

Play all 12 major scales on

your instrument. Even though each scale has a different group of notes, can you

hear that all the scales have a similar sound quality?

It's important

that you learn to recognize the characteristic sound of the major scale when you

hear it. You will learn to do this in the Ear Training module.

KEYS

| A

song melody can be played using notes from any one of the 12 major scales. The

tonic and the particular major scale used in a song determine the KEY of the song.

|

The Key is a shorthand method

of describing both the tonic and the type of scale used in a song. Thus, a song

in the Key of E♭ major means that the tonic is E♭

and the melody notes are from the E♭ major scale.

[NOTE:

There are other types of scales, but they are irrelevant for playing by ear using

relative pitch and will not be discussed here.]

EXAMPLE:

To illustrate, let's look at the opening phrase of the children's song,

"Mary Had a Little Lamb", in the Keys of C major (tonic C, C major scale) and

D major (tonic D, D major scale):

Play these two note sequences on your instrument. Do they

both sound like Mary Had a Little Lamb? They should!

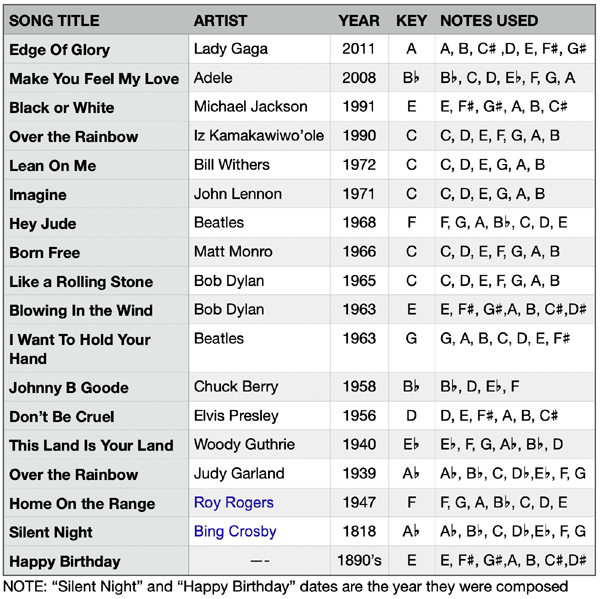

Table 2 lists 18

popular songs along with the major Keys and melody notes chosen for the commercial

recordings that we have grown accustomed to hearing.

Table 2 - 18 Popular Songs, Keys and Notes

|

•

In each of these songs the melody notes all lie in the major scale

associated with the

Key.

•

Notice that song melodies don't necessarily use all seven notes

in the major scale.

In the table, six of the songs use fewer than

seven notes - and one of them "Johnny B. Goode”, uses only

four notes.

(Although the vast majority

of popular songs are in major Keys, some songs are in MINOR keys. However, the

notes in song melodies in minor also generally lie within MAJOR scales - thus

they can be analyzed in a similar manner. We'll discuss minor Keys in the third

module.)

SCALE DEGREES

In the "Mary Had a Little Lamb" example, we found the notes

in the opening phrase in two different Keys - C major and D major:

In

D major the notes are higher in pitch, but in each Key the relationship between

the notes is the same - i.e., in each Key the note sequence pattern can be described

as:

| "Go

down the major scale from the third note to the second note to the tonic, and

then back up the scale to the second note and to the third note which is then

repeated twice." |

This

description is awkward and is not useful for playing by ear, but it can be made

useful if we simplify it by introducing a new musical term - SCALE DEGREE.

| The

seven note positions in a major scale are called SCALE DEGREES. The seven scale

degrees are named using the numbers 1 through 7, where scale degree 1 is the tonic.

A note's scale degree represents its pitch position relative to the tonic.

|

Using scale degrees,

the opening note sequence in "Mary Had a Little Lamb", in any Key, can

be written simply as

| 3

- 2 - 1 - 2 - 3 - 3 - 3 |

"Go

down the major scale from the third note

to the second note to the tonic,"

etc. |

The actual

notes in the sequence are determined by the Key of the song as was illustrated

above in the Keys of C major and D major.

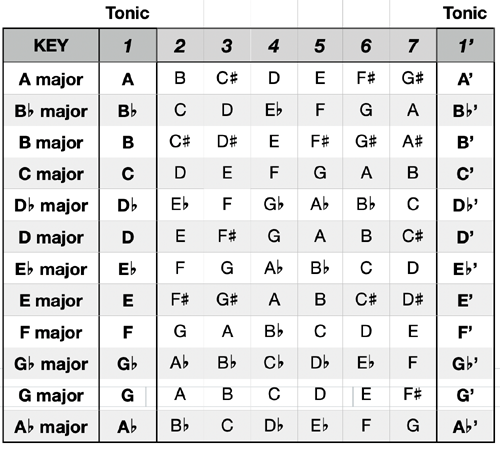

Table

3 lists the notes and their scale degrees in all 12 major Keys.

Table 3. Major Keys, Notes

and Numeric Scale Degrees

|

HEARING

AND IDENTIFYING THE SCALE DEGREES

Ok, so

how do you make use of scale degrees to identify the notes in a song you are listening

to, so that you can play it by ear?

This

is where the magic comes in . . .

| You

can train your ears to identify the scale degrees of notes you are hearing in

a song melody! |

This

is awesome!

It may sound crazy difficult,

But, it's not!

Because we humans have been listening to tonal music for hundreds (thousands?)

of years, the major scale note pattern is subconsciously very familiar

to us, even if we can't identify it when we hear it!

But, with

the proper EAR TRAINING, you can LEARN to recognize the major scale note pattern

and identify which note is the tonic and which are each of the other scale degrees.

You will learn to do this in the second module, Ear Training.

When you have a trained ear, you will hear song melodies

as a sequence of scale degrees.

For

example,

You

will hear the opening phrase of "Mary Had a Little Lamb" as 3-2-1-2-3-3-3.

You will hear "Happy Birthday" as 5-5-6-5-1'-7.

You

will hear "Hey Jude" as 5-3-3-5-6-2. |

and

so forth, for other song melodies.

PLAYING

BY EAR If you have a trained ear and can

hear and identify the scale degree of an incoming note, and you know the major

Key of the song, then from Table 3, you can identify the actual note. The Key

specifies the row in the table (the major scale); the scale degree specifies the

column (the particular note in the scale).

So, for example, in the

Key of E♭ major, scale degree 3 is the note G.

If you've

memorized the notes and scale degrees in the "E♭ major" row of

the table, then you can do this quickly for each incoming note in that Key.

In other Keys it’s the same process, using

other rows in the table. For example,

using Table 3 in the Keys E♭ major, A major, and B♭

major, the three scale degree sequences described above result in these note sequences: "Mary

Had a Little Lamb" in the Key of E♭ major is G-F-E♭

-F-G-G-G.

"Happy Birthday" in the Key of A major is E-E-F♯-E-A'-G♯.

"Hey Jude" in B♭ major is F-D-D-F-G-C. |

Voila!

So, what have we learned?

In

order to play a song melody by ear you first need to

1.

Train your ears to identify the scale degrees of notes that

you hear in songs, and

2.

Memorize the notes that go with the scale degrees in at

least one row (one major Key) in Table 3.

Then,

if you are listening to a song melody in that particular Key, you can quickly

identify each scale degree and note that you hear - and play it on your instrument.

This

is playing by ear!

SOLFEGE SCALE

DEGREES

Thus far we've been using numbers

to name the seven scale degrees. They can also be named using the Solfeggio

system (also called Solfege or Solfa). Here I will call them SOLFEGE syllables.

| The

seven scale degrees can also be named using the seven Solfege syllables: do, re,

mi, fa, so, la, and ti (pronounced doh, ray, mee, fah, so, lah, tee). |

Thus,

in the Key of C major for example, the notes and scale degrees are:

Table

4 is a reproduction of Table 3 with the Solfege scale degree names included.

In

the future, refer to this table when playing a song by ear.

Table 4. Major Keys and Numeric

& Solfege Scale

Degrees

|

You

may use either the numbers or the solfege syllables to name the scale degrees.

Each system has its merits, and each has many followers.

The number system,

sometimes called the "Nashville number system", is more intuitive since

you immediately know where any particular scale degree fits within the major scale

sequence. For example, you immediately know that the pitch of a note in scale

degree 4 is above the pitch in scale degree 3 and below the pitch in scale degree

5.

On the other hand, in the process of training your ears - ear training

- you will learn to sing the scale degrees, and the solfege syllables are

easier to sing, and they sound more pleasing to the ear.

I personally

prefer the solfege syllables, but I will use both systems here and let you make

the choice for yourself. You may want to try each system for a short while so

that you can get a better idea of how each one feels for you, but it's best

if you soon choose one system and stick with it, or else you may become confused.

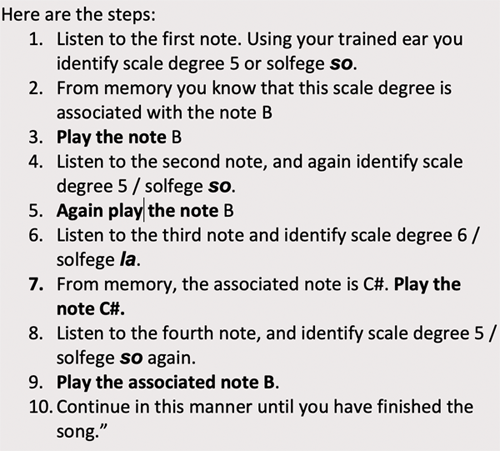

PLAYING “HAPPY BIRTHDAY”

BY EAR

Let's suppose that the “Happy Birthday”

song is running in your head and you want to play it by ear.

If 1) you

have trained your ears to identify the scale degrees of notes that you hear in

songs, and 2) you've memorized the notes corresponding to the scale degrees in

the Keys which you like to play in, then there's only one thing left to do - choose

the Key in which you will play this song.

Choosing

the Key

You don’t know the Key of the Happy Birthday song that

you are hearing., so what do you do then?

You can identify the tonic

note of the major Key using your instrument. The tonic is scale degree 1.

If you're able to hear and identify scale degrees, then simply sing the note corresponding

to scale degree 1. To identify that note, using your ear and trial & error, find

the note on your instrument that matches that pitch. Suppose you do this and find

that the tonic note is E. So, now you know you are hearing the Happy Birthday

song in the key of E major.

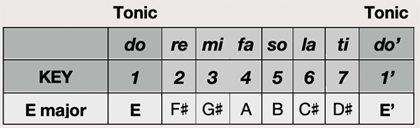

Playing “Happy

Birthday” in E Major

If you're comfortable playing your

instrument in this Key, E major, and you’ve memorized the notes that go with the

scale degrees in this Key - i.e., the notes in the E major row of Table 4 - then

you can proceed to play the melody by ear.

|

These

steps go very quickly if you’ve trained your ears to hear scale degrees and you’ve

memorized the notes that go with the scale degrees in E major.

Hearing

the song in another Key

But what if you aren’t comfortable

playing your instrument in E major? Ideally, you would be comfortable playing

your instrument in any Key, and you would have memorized the notes vs scale degrees

in all 12 Keys, in which case you would play the melody in the same Key that you

are hearing it - whatever the Key may be.

But, this is not usually

the case. All musicians have their favorite Keys to play on their instrument.

And there are some Keys that almost no one likes - like F♯ major

or B for example - Keys with several accidentals (sharps or flats) in the major

scale. What if the song melody in your head is in one of those Keys?

Let’s suppose you would prefer playing the song in the key of G major. That’s

OK, but you must remember that the basic rule of playing by ear is:

You must play the song in the same Key that you are

hearing it - otherwise your ear will become terribly confused.

So, if you want to play the song in G major, then you

must first learn to HEAR the song in G major.

The best way to do

this is to sing the melody in the new Key a couple of times, until your ear

becomes acclimated to the Key.

But some people have difficulty singing

a melody in different Keys. It can be tricky. To test yourself, play any note

on your instrument and try to sing Mary Had A Little Lamb with that note as

the tonic (the last note in the melody). It's especially tricky with this

song because the melody doesn't begin with the tonic note - it begins on scale

degree 3.

There are many ways to do this,

but if you have a trained ear, a good way to sing Happy Birthday in a new Key

is to:

| 1) | Identify

the scale degree of the starting note - for Happy Birthday that would be scale

degree 5 / solfege so. | | 2) | Using

your instrument, play the tonic note in the new Key - the note G. | | 3) | Sing

the major scale in the new Key - to acclimate your ear to the Key. Then | | 4) | Sing

the starting note in the new Key - scale degree 5 / solfege so (the scale degree

that you identified in step 1). |

When

you sing the starting note, and your ear is attuned to the new Key, you will quickly

recognize the melody and be able to sing it. Sing the melody until it is internalized.

Once you are hearing the melody in the new Key, G major, then you can

play it by ear just as was explained above in the Key of E major.

The

general two-step method is: For each melody note, 1) identify its scale degree

(using your trained ear), and 2) in the Key of the song, play the (memorized)

note associated with that scale degree.

Using this method you can play all song melodies in the same Key if you wish

- good if there is only one Key that you feel comfortable with on your instrument.

However, it's advantageous if you can (comfortably) play your instrument

in more than one Key. Then the song melody in your head is more likely to be in

one of your "comfortable" Keys - in which case you won't need to change the Key.

SUMMARY/REVIEW

Now we're

home!

As soon as you 1) develop a musical ear and can hear and identify scale

degrees, and 2) memorize the notes that go with the scale degrees in at least

one Key, then you'll be ready to play a song melody by ear.

Let's review

the steps - there are three parts:

Part

1 - Do your homework

| 1. | Ear

training - learn to quickly identify scale degrees of notes that you hear

in songs (go to the Ear Training page on this website) | | 2, | Memorization

- memorize the notes that go with the scale degrees in the Keys that you prefer

playing on your instrument (use Table 4). |

Part

2 - For the particular song that you want to play by ear, hear the song melody

in the Key that you want to play in.

| • | Identify

the Key of the song you are hearing (using your instrument). | | • | Choose

the Key you will play in. | | • | Hear

the song melody in that Key. |

Part 3 - Play the song melody (in your chosen

Key)

For each melody note that you hear:

| • |

Identify the scale degree (either the number or the Solfege syllable), using your

trained ear. | | • | From

memory, identify the actual note in your chosen Key. | | • | Play

the note |

|

Now that

you understand the playing-by-ear process, it's time for you to begin doing the

homework. In the Ear Training page of this website you will find several exercises,

songs, and references to other ear training resources that will help you learn

to identify the particular distinctive sound associated with each scale degree

in songs that you are listening to.

See you there! |